The production design of Blade Runner (1982)

Director: Ridley Scott

Production designer: Lawrence G. Paul

Summary

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner might have been a critical and financial disaster in 1982 but time has transformed it into one of the most significant films in human history. Unpacking Blade Runner both thematically and visually is a daunting task even after four decades. Yet, aesthetically, it remains a landmark reference whose visual look is being emulated (most of the times) poorly by others. How many times have you read that a movie or a video game has a Blade Runner feel to it?

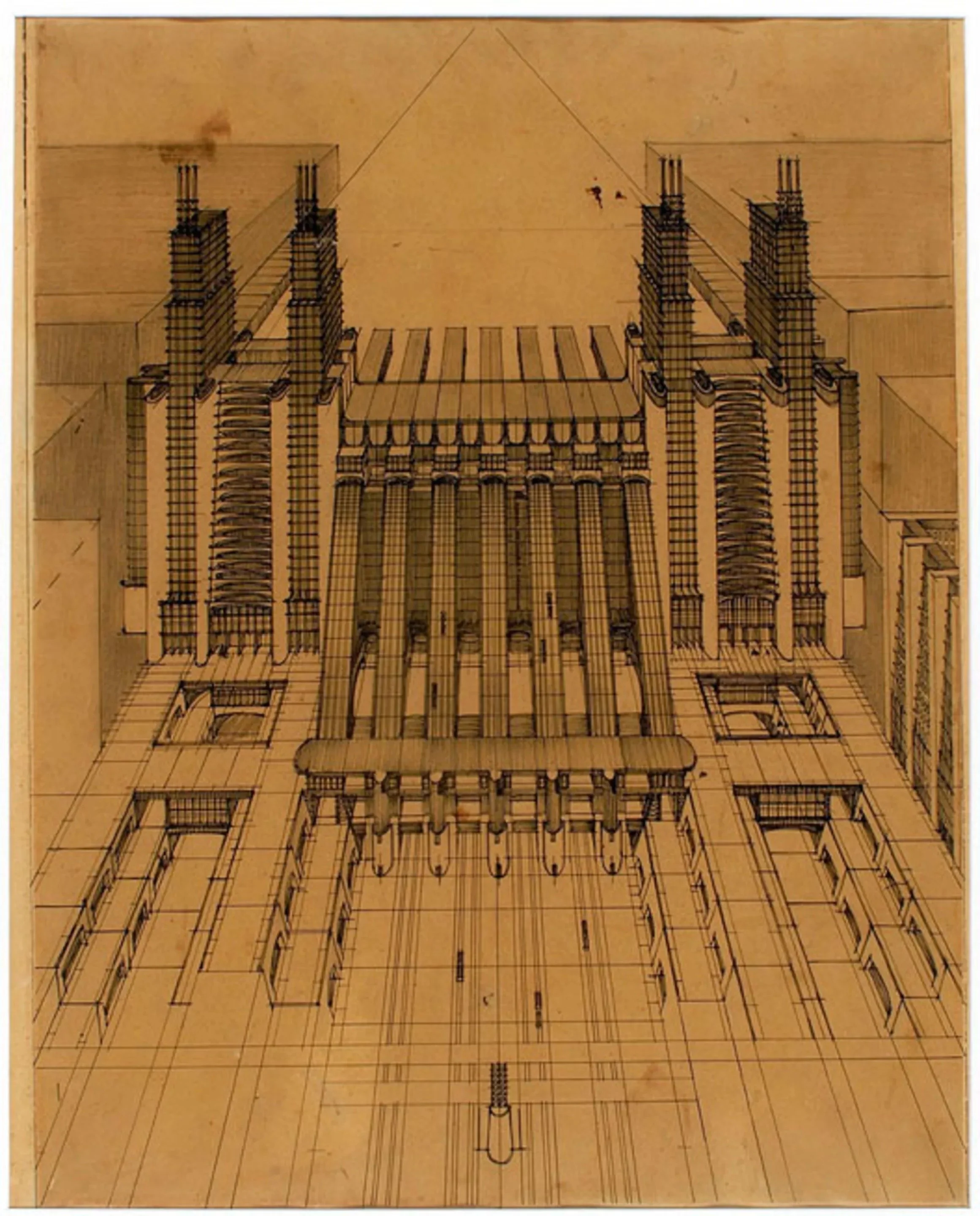

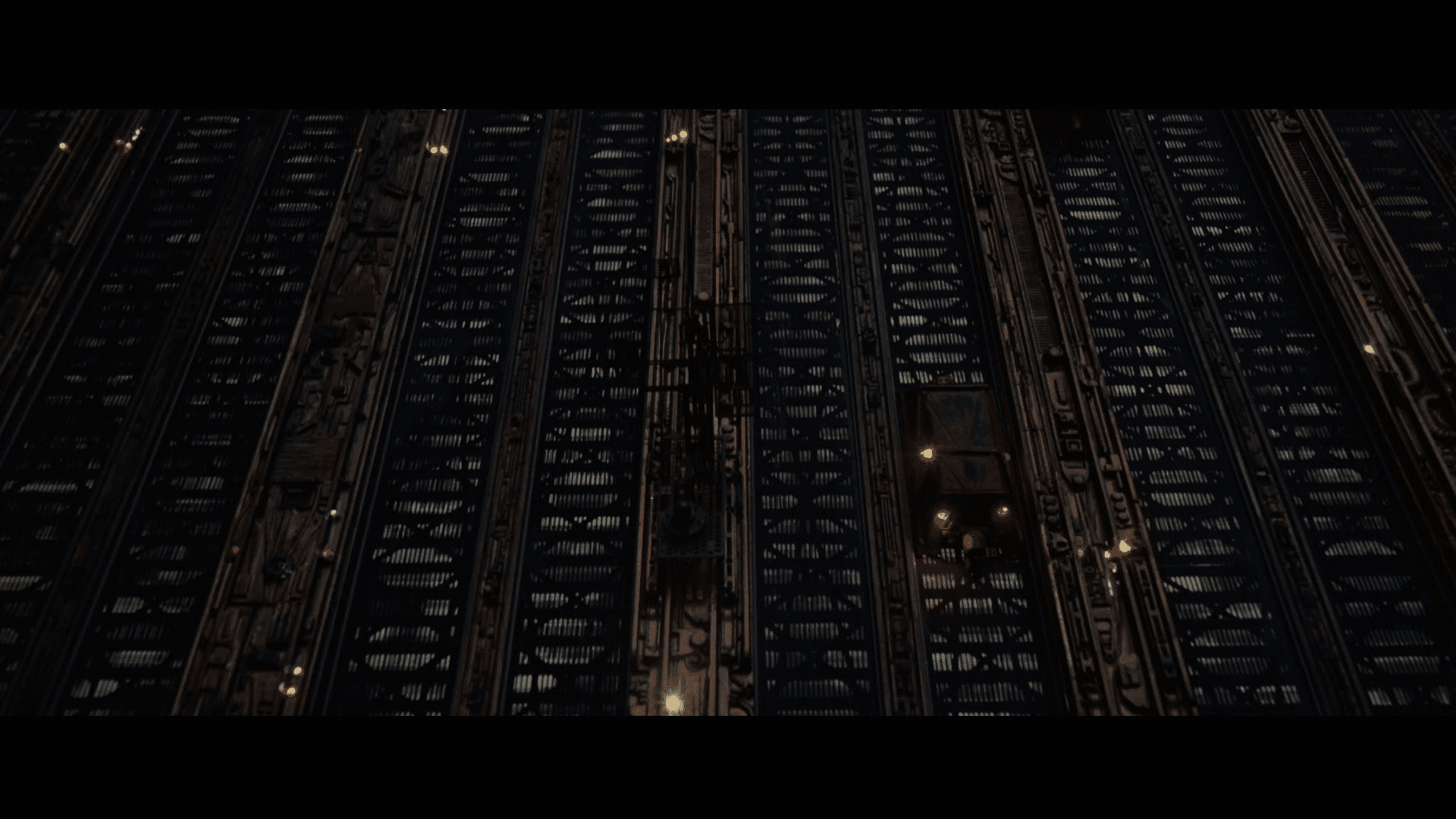

Lawrence G. Paull’s work here set the foundation for believable science fiction set in a dystopian world elevated by the ground-breaking designs of Syd Mead, the guy responsible for conceiving and designing the spinner, the sedan shapes, the retrofitted retro Deco future, and the “layered city” verticality. Along with Scott, all three took inspiration from several sources to bring to life something that was not done before: a rainy, industrial-dominated Los Angeles full of neon signs, Asian and cyberpunk sensibilities with ideas from futurist architect Antonio Sant’Elia and giant screens alongside never-ending skyscrapers promoting things like Coca-Cola.

Blade Runner’s L.A. is not just a dystopian, foggy and metallic landscape - it is a place that exacerbates the worst elements of Metropolis (1927), a place where the wealthy live above the workers in massive man-made structures like the Tyrell corporation’s gargantuan pyramid. Scott added extra elements in his degraded Metropolis-like motion picture such as the industrial landscape of his home town Teesside in the UK and the look of Hong Kong on a very bad day (i.e., filled with smog and clouds). This choice resulted in generating the most original vision for a science fiction film and the gold standard against which all cyberpunk dystopias are measured.

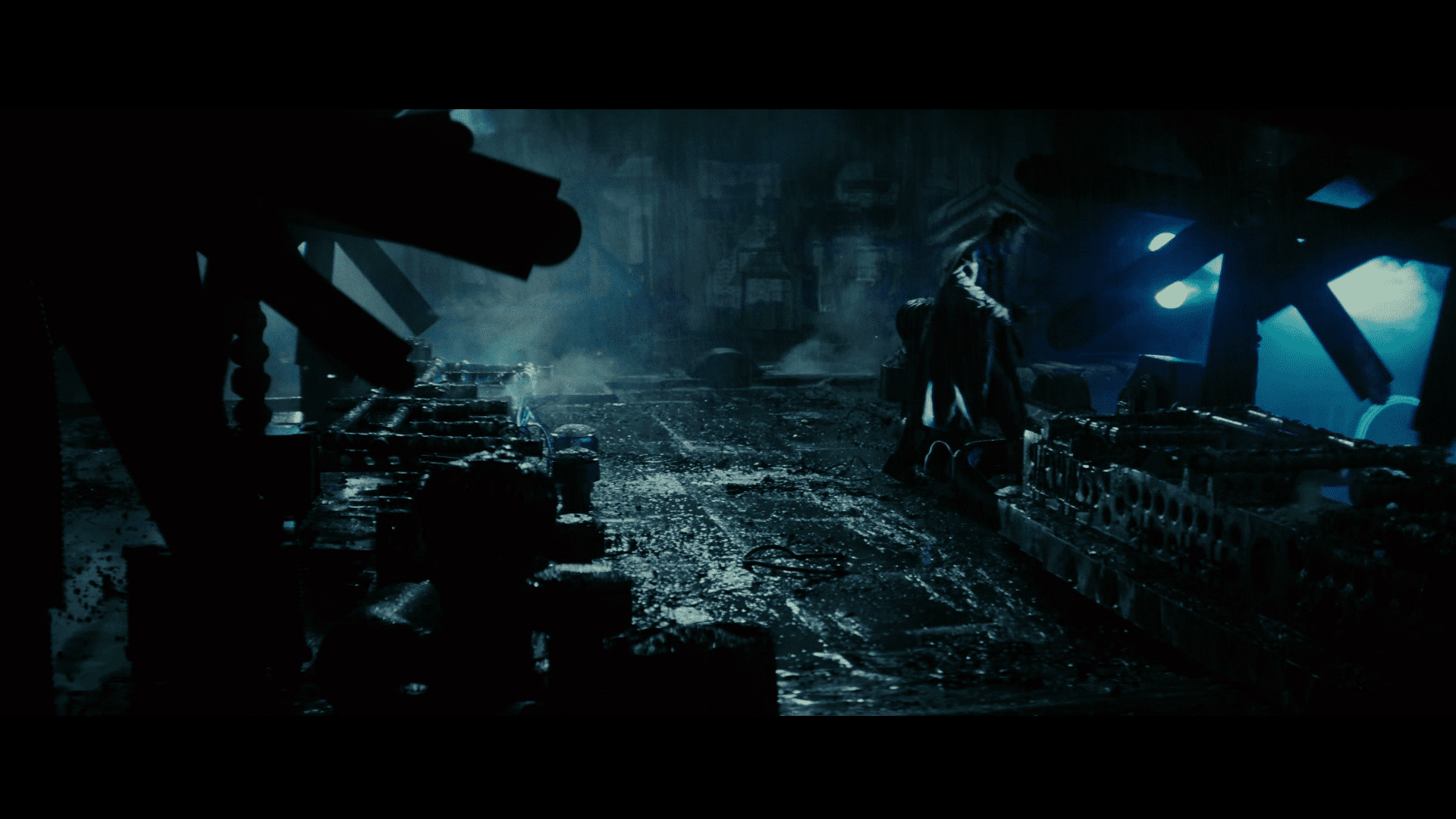

Other sources of inspiration included the French science fiction comics magazine Métal Hurlant, whose hyper-stylized, pioneering aesthetic for the 80s was pivotal for Blade Runner’s sensationally moody production design that represents a barely functional world that has fallen into disarray and decadence; Edward Hopper’s painting Nighthawks for bars, noodle shops and residential flats, all of which bear a distinct visual identity; Joan Crawford for Rachel’s style and wardrobe, which now feel more anachronistic than it did in the 80s; and Miss Havisham's room in Great Expectations (1946) for J.F. Sebastian's cluttered apartment of robots and antique furniture that seems to have a history of its own in the now famous Bradley Building in L.A.

Colours

Black chocolate, pastel grey, medium jungle green, umber, khaki, rick black, dark gunmetal, dirt, blue sapphire, dark green, seal brown, Vegas gold

Influences

Teesside industry

Hong Kong

Antonio Sant’Elia

Metropolis (1927)

Joan Crawford

Metal Hurlant comic

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks

Great Expectations (1946)